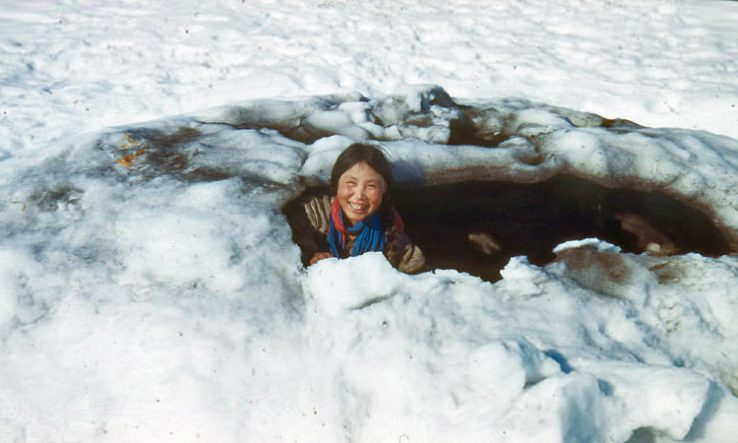

Image: Library and Archives Canada / Bibliothèque et Archives Canada [CC BY 2.0], via Flickr

A rare opportunity to work with Inuit communities hit by climate change

The Understanding Environmental Change in Inuit Nunangat—the Inuit homeland in Canada—is a call launched by UK Research and Innovation along with five Canadian funders.

The scheme, launched on 9 June, will fund research proposals that investigate climate-driven changes to the environments in the homeland of the Inuit in Canada, as well as the impacts on the Inuit community itself. UKRI’s Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council and the Economic and Social Research Council are all involved.

The total amount of funding available through the call is approximately CA$6.9 million (£4m) from Canadian partners and £7.6m from UKRI. For UK applicants, each project will be awarded up to £545,000 each at 80 per cent of full economic cost. The deadline for letters of intent, which will be evaluated for fit to the call, is 4 August 2021 and the deadline for full proposals is 10 November 2021. The funders aim to support around 14 projects.

Henry Burgess, head of NERC’s arctic office, Lizzie Garratt, head of atmospheric and polar at NERC and Jessica Surma, senior programme manager for polar and marine at NERC, lay out the essentials.

What are the main aims?

There are two main themes: the first is Arctic ecosystems and their impact on Inuit communities, and the second is mitigations and adaptations for resilience. There are also three cross-cutting issues: the economics of Arctic change; resilience and sustainability; and Inuit community health and wellbeing. Each application must apply to one theme and cover at least two of these three cross-cutting issues.

The call also recognises that there is an increasing need to connect properly with the communities that live in the Arctic—not to study them or to offer them results but to include them as researchers and full partners within the study. This the right thing to do but it also engenders better science; those living in the Arctic have all kinds of skills that western researchers don’t. The impact that any proposals will have on Inuit communities, as well as the impact more broadly on UK-Canadian understanding of environmental change will be an important issue when we evaluate proposals.

Is interdisciplinarity a must?

Very much so. We want to make sure that we include people from environmental, social, economic, health, cultural, design, engineering and infrastructure backgrounds. That’s not to say that UK applicants should cover the full breadth. It may be that some disciplines are covered on the UK side and others are covered on the Canadian side. But one tip we would give to applicants would be to make sure their project is integrated rather than a series of standalone sections. For example, there may be a biology component, a social component and a climate component—these should be integrated and related.

What kinds of applicants are you looking for?

We are looking for people who are keen to build new partnerships. On the Canadian side, we are encouraging the principal investigator to be a member of the Inuit community. If not, the project must include a funded member of the team from this community. Within Inuit communities, there are both “classic” researchers—such as scientists—and researchers who are hunters, trappers or specialists in areas that UK researchers do not specialise in.

Do you expect UK applicants to have previous experience working with Arctic communities or in Arctic environments?

While we do expect that the call will be of interest to those with experience working with Inuit communities, it is not a prerequisite. Given the breadth of disciplines needed, we expect that team members may be applying their expertise in a new setting here.

What are your expectations regarding partnerships?

Co-development is the watchword. The expectation is that researchers in both countries will co-develop the proposal and work alongside each other. Then, when the work is complete, they will share publications, data and the management of that process. So, while the funding streams are different, the researchers doing the projects should be part of a single team.

Will UKRI help with matchmaking?

Yes, there will be an online collaboration platform where people can lay out their expertise and idea and ask those who are interested in teaming up to get in touch.

Any final advice for applicants?

Yes—as well as funding on the Canadian and UK sides, there is also a big offer of in-kind contributions. That could be use of a boat or helicopter, time in a research station or field support. There is no need to give details of this in your letter of intent, but people should bear in mind that those possibilities are out there. And that they should start those conversations early because a lot of the fieldwork costs could potentially be covered through that route.

This is an extract from an article in Research Professional’s Funding Insight service. To subscribe contact sales@researchresearch.com