Norwegian researchers explain how to get rapid clinical trials off the ground

One of the many ways the coronavirus pandemic has changed the research landscape is the emergence of global mega-trials for medications against the disease.

In March, the World Health Organization launched the Solidarity clinical trial, an international effort to test four potential treatments for Covid-19, in response to concerns that large numbers of small-scale trials would make it difficult to compare results. The core protocol of the Solidarity trial was designed so that research groups worldwide could easily take part, and more recently the WHO has proposed a similar international trial for the large number of vaccine candidates in development.

Building solidarity

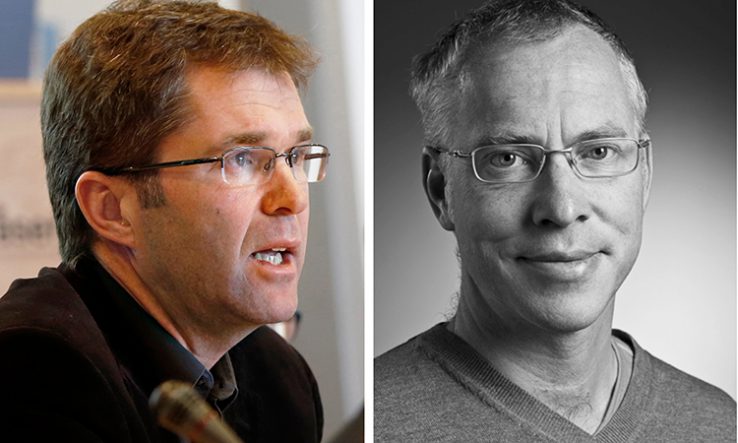

John-Arne Røttingen, the chief executive of the Research Council of Norway and chair of the international steering committee behind the Solidarity trial, explains that while the WHO is coordinating the work, research groups need to apply to funders in their home countries in order to join the trial.

“The normal mechanism, at least in Europe, will be that countries will need to finance their part of the trial because WHO has not set up a large financing mechanism for this,” Røttingen says.

The situation for developing countries is a little different because WHO can help facilitate trial funding, he says, even if it cannot directly fund them. And Røttingen points out that some of the money raised through a global pledging conference on 4 May will go towards research.

“There will be new opportunities and calls where researchers can contribute,” he says.

For any research group wanting to take part in the trial, Røttingen says the first step is to contact the WHO trial centre to check if there is already a group established in the same country. He says that while it is possible to have more than one group per country, “the normal situation would be that there will be one coordinated trial”.

First response

Andreas Barratt-Due, a specialist in anaesthesiology and intensive care medicine from Oslo University Hospital, is coordinating the Norwegian arm of the Solidarity trial. On 27 March, his trial was the first to enrol a patient in Solidarity.

Barratt-Due says his group was quick off the mark due to early engagement with the WHO’s R&D blueprint, which is the mechanism set up to coordinate research during epidemic emergencies. He and his colleagues started talking about running a trial at the end of the February, when Norwegian holidaymakers were coming back from ski trips to the Alps, potentially bringing the virus with them.

He recalls thinking “we now have this opportunity to contribute to the WHO database and we should really try to join this”, so he set out designing a trial protocol as fast as possible. “I think I wrote this protocol in 24 hours.”

After designing the protocol, Barratt-Due contacted all the hospitals in Norway to ask if they wanted to take part. “They were all very eager to join, and this was before we had any approval,” he says.

Barratt-Due says it was the momentum of having so many hospitals interested in taking part that meant funding was forthcoming. They held a press conference on starting a trial in Norway, which received widespread media coverage, and after that they heard from the Norwegian health authorities that they would support the trial.

“I think the health authorities understood that a randomised controlled trial would need support, and decided to provide grants before any application was delivered,” he says, sounding somewhat surprised about how events unfolded. “This is a huge amount of money; the budget is around 20 million Norwegian kroner (€1.8m).”

Meeting with approval

Even with funding, individual clinical trials need to go through national ethical and regulatory approval before being able to enrol patients in the WHO trial, and this is a process that can vary from country to country.

Røttingen says that once the protocol is validated and applications have been made for ethical and regulatory approvals, then a trial can be accepted as part of Solidarity. “There will be a memorandum of understanding or a joint understanding between WHO and the country’s minister of health, or the leading hospital or the coordinator of the trial,” he says.

The Norwegian group managed to get through the approvals process quickly through sheer hard work. “We worked like mad for almost 18 hours a day just to finish everything,” Barratt-Due recalls, adding that “we managed to include the first patient two-and-a-half weeks after we started.”

He says the WHO protocol is “very, very simple”, only requiring them to report whether or not patients survived or needed intensive care. “We decided that, if this is something we should do, then we should learn more,” he says, so they added a number of further measurements to enrich the results.

In addition, the Norwegian researchers chose not to test all treatments in the WHO protocol, partly due to fears that one of the treatments, involving interferon-beta, could exacerbate symptoms in patients.

“We said to WHO that it is impossible to include all four treatment arms at the moment,” says Barratt-Due. Instead they started with just one, hydroxychloroquine, and then added another, remdesivir, later on.

Barratt-Due says that close communication with the WHO was crucial in agreeing on how they would run their arm of the trial. “We have tried out different solutions,” he says, “and we have been able to give fruitful feedback.”

While hospital admissions for Covid-19 in Norway have been dropping as the crisis has been brought under control, Barratt-Due is hopeful their results will have strengthened the global evidence base for treatments. He says that during the Ebola crisis, very little was learned about which treatments were successful.

“That could be the case after the coronavirus crisis,” he says. “That has been the biggest motivation.”