Image: Oregon State University [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Flickr

Researchers may want emergency measures to continue, but public trust has eroded, says Cian O’Donovan

British Summer Time was an emergency measure, brought in during the First World War to maximise daylight hours for agriculture workers. A century later, we’re still changing our clocks twice yearly.

Measures brought in during crises, in other words, have a way of becoming permanent, and of being applied in situations beyond those used to justify them. As the crisis stage of Covid-19 ends in the UK, a review of the temporary pandemic measures is now in order.

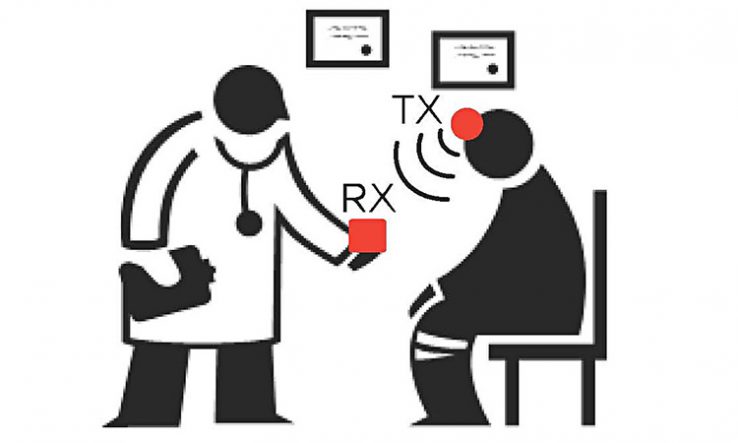

On research data, one key policy tool has been control of patient information (COPI) notices. It is usually illegal to share patients’ identifiable information without their consent for purposes beyond their individual care. COPI notices can not only make this legal, but require GPs or other NHS stakeholders to do so. Issued by the health secretary, these allow the processing of usually confidential information, such as GP health records, for specified purposes.

One COPI notice, for instance, requires GPs to supply UK Biobank—a huge biomedical database that integrates the genomic and health records of a cohort of 500,000 consented patients—with their data about its cohort. This can then be released to researchers working to understand the virus and its impact on individuals and populations.

Other COPI notices have gone to NHS Digital, NHS England, GPs and local authorities, allowing them to process a wide range of confidential information without seeking patient permission, in the name of tackling Covid.

COPI notices are a means of prioritising one set of ethical values over another. During the pandemic, research practices that placed a premium on patient privacy have been traded for fast-flowing data.

These notices need to be renewed every six months; unless NHS Digital requests another extension, the current batch will expire in March 2022. At some point, the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) will have to decide which measures to keep, what to adapt, and what to decommission.

The game to muster influence is already afoot. Experts in data science and artificial intelligence, convened by the Turing Institute, have noted that “consideration might be given to how the best aspects of COPI might be retained, whilst ensuring that the permissiveness does not undermine individual rights and protections”. The notice granted to mandate UK Biobank is itself a sign that large research projects can shape data regulation.

There are important points on all sides. Researchers using the data are reluctant to give up their productivity gains. Privacy and open-science advocates want to shine a light on the infrastructure for public health data.

Perhaps the clearest argument is this: there is still lots of science to do. The data, disease specialisms and disciplines needed to understand long Covid, for example, remain uncertain. Keeping the data flowing will probably help.

Reluctance to let go

Data infrastructures and data governance arrangements at the start of the pandemic were not as good as they should have been, according to the Coronavirus: Lessons Learned to Date report, published by two parliamentary committees in October. Some researchers are likely to see COPI notices as a means of doing things that they should already have been able to do. They will be reluctant to let them go.

This stance, though, risks overlooking the dramatic shift in public attitudes around how data are collected and used. Moves to use emergency measures to drive post-pandemic data strategies must contend with increasing strains on citizens’ confidence in public data.

This was evident in the summer, as the health department and NHS Digital were caught on the hop during the long-planned rollout of the General Practice Data for Planning and Research programme. In June alone, more than 1.2 million people opted out of sharing their GP data. They were unwilling to grant GPDPR a social licence to operate, despite data-protection laws and assurances from NHS Digital.

The controversy shows that the debate around data and trust has changed. This is no surprise. Parliamentary committees have challenged the public value of the huge spend on NHS Test and Trace, and campaigners against NHS privatisation have objected to the decision to pay the US tech company Palantir £23 million to run the Covid-19 Data Store. If data controllers are struggling to gain trust, it is because goodwill has been squandered during the pandemic.

Policymakers must recognise these changes in the social context in which data are collected and used. We don’t know what the public thinks of COPI notices because they haven’t been asked. Neither do we know much about their long-term impact on research, although work by the PHG Foundation is due on this soon.

At bottom, researchers’ desire to get their hands on patient data may be in tension with their need to get patients to trust the system enough to share their data. Patients are reassured that their data will only be shared anonymously, but each COPI notice is an instance where that has not been the case. So who can blame patients for withdrawing consent to share data, full-stop?

Meaningful involvement

NHS Digital cannot afford another GPDPR-style controversy. Recent research by the UK Pandemic Ethics Accelerator shows that, when asked, people said they want trust in institutions to be improved and they want meaningful involvement in pandemic policymaking. Without this, further build-outs from emergency data measures risk perpetuating a cycle of distrust that might take years to remedy. This point was emphasised by the National Data Guardian, Nicola Byrne, who recently warned that emergency powers brought in to allow the sharing of data to help tackle the spread of Covid-19 could not run on indefinitely.

Policy for public data needs to address the following. First, data institutions must show they can be trusted and make a better case for public benefit. For instance, any process to make COPI notices permanent should be accompanied by public dialogue and open debate. The DHSC, NHS Digital and the UK genomics community must make the case stating how public data benefits us all.

Second, data projects must work out how to address individual and collective concerns together. Debates should not be reduced to individual privacy versus population health.

It looks likely that COPI notices will be renewed again in March 2022, but possibly with the proviso that this is the last time. That gives data controllers and users just under a year to build trust by making a better case for why we all should buy into these benefits. That is less time than it might seem.

Cian O’Donovan is a researcher at the UK Ethics Accelerator, working from the Department of Science and Technology Studies at University College London